"Had I the divine right of learning..."

A reading companion for An Immortal Book; launching Cita Studio; Leap Day lore!

Happy Leap Day! As promised, we’re closing out February by launching our new reading guide for An Immortal Book: Selected Writings by Sui Sin Far. We also share a glimpse of Cita Studio, the new design and editorial services branch of Cita Press. Finally, we wrap up with some funny-but-also-earnest feminist Leap Year content courtesy of Nellie Bly.

The Divine Right of Learning

In the short story “The Inferior Woman,” Mrs. Spring Fragrance tells her husband about the potential she sees in her white neighbors’ personal drama. If only she was qualified, she asserts, she would adopt the role of cultural anthropologist and dig into the greater meaning behind the gossip:

“Ah, these Americans! These mysterious, inscrutable, incomprehensible Americans! Had I the divine right of learning I would put them into an immortal book!”

“The divine right of learning,” echoed Mr. Spring Fragrance, “Humph!” Mrs. Spring Fragrance looked up into her husband’s face in wonderment.

“Is not the authority of the scholar, the student, almost divine?” she queried.

“So ’tis said,” responded he. “So it seems.”

Mrs. Spring Fragrance takes Mr. Spring Fragrance’s hesitation as the validation she needs to embark upon the project:

“I desire to write an immortal book, and now that I have learned from you that it is not necessary to acquire the ‘divine right of learning’ in order to accomplish things, I will begin the work without delay.”

While putting together An Immortal Book: Selected Writings by Sui Sin Far, it became clear that Mrs. Spring Fragrance’s repeatedly-stated desire to writing a significant book was an echo of Sui Sin Far/Edith Eaton’s own ambition as an author.1 Thus, it seemed appropriate to borrow Mrs. Spring Fragrance’s framing for the title of our collection of Eaton’s work.

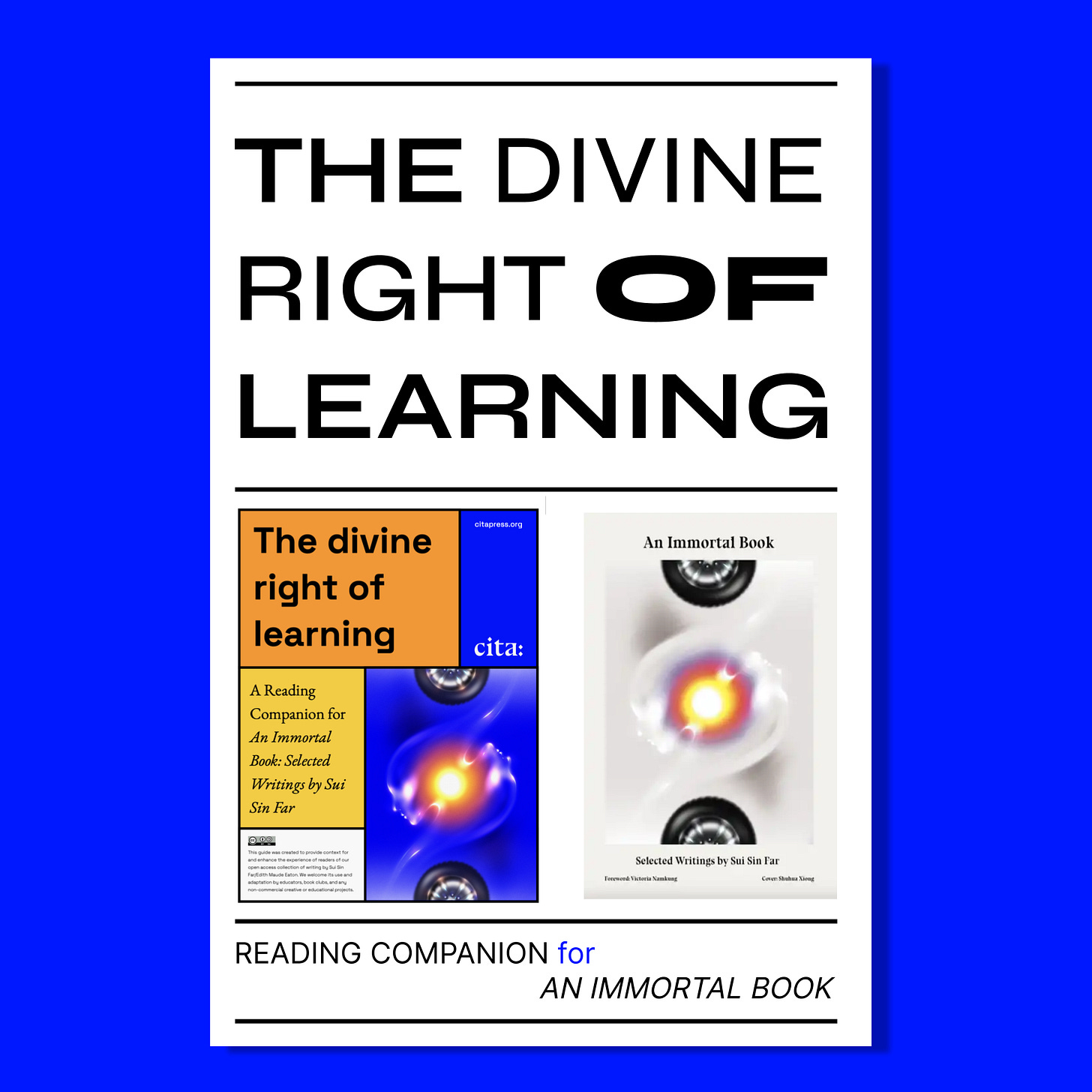

Now, we present something new that also draws its title from the Spring Fragrances’ conversation: “The Divine Right of Learning,” a downloadable reading companion for An Immortal Book.

When Mrs. Spring Fragrance decides that she doesn’t need some kind of official permission to write her immortal book, she takes a position that is core to Cita’s ethos. All kinds of people have produced meaningful knowledge and created significant art throughout history. Some of those people embarked on their work buoyed by societal and institutional positions that made them sure of their “divine right.” Others—like Sui Sin Far, whose gender, race, and education level didn’t match the circumstances of her most visible peers—went to work fueled only by personal determination and passion.

“The Divine Right of Learning” is for any reader who comes across Sui Sin Far’s work and decides to learn more about the author and the context of her work. Whether you are a casual reader, a student working on a project, an educator preparing a lesson, a book club member looking for help guiding discussion, or just a person online looking for something interesting to skim, we hope that you find it useful.

The guide is designed to be modular, with four main sections that can be consumed together or separately:

A biographical sketch of Sui Sin Far/Edith Eaton and her fascinating family.

Overviews of two areas of historical context, with corresponding story excerpts:

Chinese Exclusion in the United States in Canada: in both countries, Chinese Exclusion marked the first instance of race-based immigration policy.2

“The New Woman:” The often-contradictory application of this cultural ideal reflects varying impacts and interpretations of rapid social change.

An exploration of how some feminist themes pop up in Sui Sin Far’s writing.

Two appendices digging deeper into reception of Sui Sin Far’s work and how people engage with it today.

Thank you to everyone whose work and feedback went into this guide. If you have questions about the content or process, please feel free to reach out via jessi@citapress.org. For further exploration, check out the resources in the bibliography and our dedicated Are.na channel.

Introducing…Cita Studio!

Cita Press is pleased to share that we’ve officially launched our design and editorial services arm: Cita Studio! Cita Studio provides services—including brand identity packages, publication cover/interior design, and editing—to companies, organizations, and individuals. If you or your company is looking for help with a book project, a company manual, a brand revamp, reach out to start a conversation!

By working with Cita Studio, our clients directly support the Press’ library of free feminist books. Learn more by visiting cita.studio. ✨🤗

Leap Day’s Feminist Lore

Did you know that a tradition permitting women to propose marriage only during a Leap Year was taken quite seriously in some parts of the world—for centuries?

According to legend, “Bachelor’s Day” or “Ladies’ Privilege” began in Ireland as a result of a pact made between Saint Bridget and Saint Patrick. From there it traveled to Scotland and England, where it was even codified into local laws. Practices around the tradition varied, and they expanded to include compulsory gifts from men should they turn down proposals (silk dresses, gloves, a kiss) and customary outfits for the women doing the proposing (red petticoats!).

By the mid-1800s, the tradition was used as a way to mock women who dared to take their fates—romantic or otherwise—into their own hands. As women gained rights and opportunities throughout the century,3 jokes about rabid spinsters hunting bachelors on Leap Day abounded in the media.

Not everyone thought that reversing proposal norms was something to scorn. You may know of Nellie Bly as a pioneer of stunt journalism, but she got her start after penning a feminist polemic addressed to the editors of her local newspaper (later published as “The Girl Puzzle”). She continued arguing for women’s rights in print throughout her career. In 1888, she used the Ladies’ Privilege tradition to not only assert that women should feel free to propose in any year, but also to celebrate the professional gains many women had made in the preceding decades. Featuring humorous, revealing interviews with a motley cast of characters and playful commentary that belies her almost radical stance, “Should Women Propose?” makes for an entertaining read. See a scan of the original and some related images on our Are.na; read Cita’s transcription here.

“The social rules which govern love teach a girl to hide every sincere feeling and to pretend what she does not feel, yet those who would be first to cry ‘Shame!’ at a woman for deceit would be the first to cry ‘Bold!’ if she gave evidence of her true feelings.”

—Nellie Bly, “Should Women Propose?”

Similarly, her frequent remarks about the “mysterious” nature of Americans mirror rhetoric from popular depictions of Chinese immigrants— a perfect example of Sui Sin Far’s sly humor.

Familiarizing yourself with the basic facts of this period may cause instant déjà vu when reflecting on things we see today…

See the section on “the New Woman” in our aforementioned reading guide.