"...you might arrive at yourself."

On legacy: marking 'firsts' vs. mapping relationships; Edith (Sui Sin Far) & Winnifred (Onoto Watanna) Eaton; Miné Okubo, Diana Chang.

When discussing women writers from the past, marking “firsts” is an efficient way to place lesser-known names in a larger context. Depending on their background or interests, many people may not recognize the name “Lady Murasaki,” for example—but they can probably grasp the significance of “the world’s first novel.”1 It’s fun to highlight how many feats challenge the perception that contributions by women were late and few—and tracing this history has deep roots. From Christine de Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies to Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own to Alice Walker’s In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens and beyond, a simple inquiry—“Who did this before me? And before her?”—has inspired countless writers to imagine a future that not only acknowledges, but actively learns from, the work of feminist forebears.

There is also, of course, danger in leaning on “firsts” as a way of defining any writer’s worth. What is the value of tracking accomplishments in chronological order if a voice is heard but not listened to; if work is acknowledged but not engaged with? The promise of legacy—of being recognized in death if not in life—can be big or small consolation depending on the form it takes.

In “Leaves from the Mental Portfolio of an Eurasian,” Edith Maude Eaton predicts how the passage of time might put a sheen on the struggles she endures as a half-white, half-Chinese woman writer during a time where racism and legal exclusion is the default. Published under Eaton’s pen name, Sui Sin Far, the 1909 essay lays out how her background, ambitions, and ideals shape the author’s personal and professional life. “I cheer myself with the thought that I am but a pioneer,” she explains, “A pioneer should glory in suffering.”

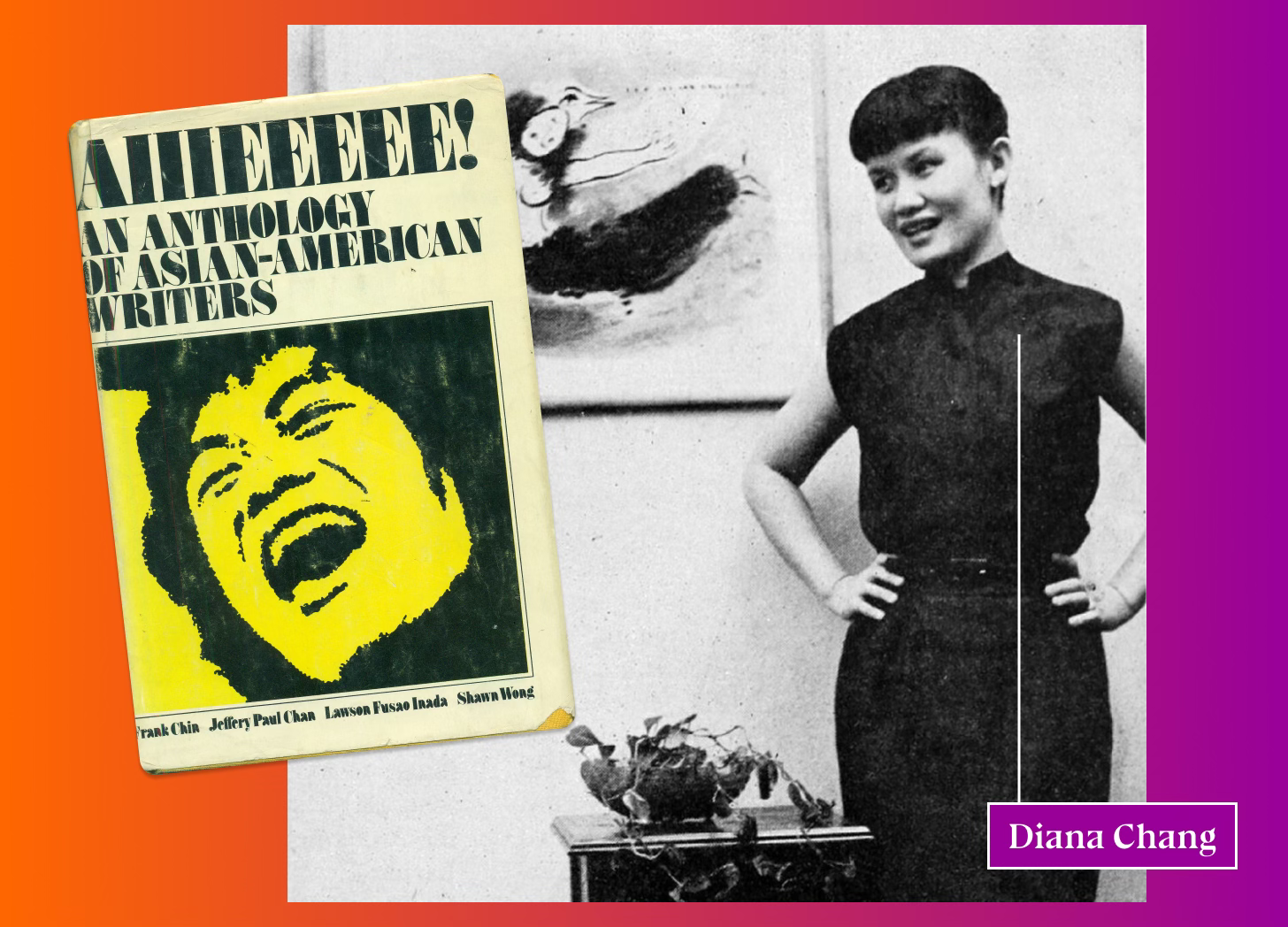

Sui Sin Far’s status as pioneer has been cemented in the century-plus since she claimed the title. Though she died in 1914, at just forty-nine, she left behind a significant body of work. Many point to Eaton’s story collection Mrs. Spring Fragrance (1912) as the first book published in the United States by an author of Chinese heritage. Others have called her the “mother of Asian American literature.” Despite these lofty labels, she was also the named example of “unstudied, unread, unknown Asian Americans” for editors Frank Chin, Jeffrey Paul Chan, Lawson Fusao Inada, and Shawn Wong in the preface to the 1991 edition of Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian-American Writers. Though recognition is growing, it’s taken too long for Eaton’s legacy to reach the full glory her suffering earned her.

When putting together “The Divine Right of Learning,” the reading companion to Cita’s 2023 open access collection An Immortal Book: Selected Writings by Sui Sin Far, we asked a handful of scholars and writers about how they first encountered Eaton’s work. Mary Chapman, Cherrie Kwok, Victoria Namkung, and Anran Wang all found her in university classrooms, introductions that sparked years-long study across topics and disciplines. Recent conference programs have indicated a growing interest in her work within academia, and—given her work’s accessibility, humor, and still-timely concerns—it seems likely that this trend will continue to include more casual readers (and we hope our collection can help with this!). However, thinking about the relationship between Sui Sin Far’s fame as a “first” and actual engagement with her writing raises a larger question of how writers become studied, read, and known in the longer term, and how such engagement changes to reflect society’s interests.

Who builds a legacy?

While an author lives, they are the primary steward for their own legacy. This depends most of all on their writing, of course, and then their ability to promote it and connect with champions—editors, publishers, journalists, fellow writers. After death, however, the shape of that legacy is out of their control. As we often see with women writers, even a prolific catalog from a bold voice can quickly fade to obscurity without institutions and gatekeepers invested in keeping it visible.

We first see coverage of Sui Sin Far as a literary figure when she is around thirty-five years old, over a decade into her writing career and a few years into using a variation of her pseudonym. In the November 1900 issue of Land of Sunshine, editor Charles Fletcher Lummis describes her like this: “So far as I know, the only Chinese woman in America who is writing fiction is the delicate little Sui Sin Fah, a 'discovery’ of this magazine three or four years ago.”

He moves on to her work:

Her stories in these pages have been widely copied; and while they lack somewhat of literary finish, they merit the attention they have attracted…They are all of Chinese characters in California or on the Pacific Coast; and they have an insight and sympathy which are probably unique. To others the alien Celestial is at best mere '‘literary material’; in these stories he (or she) is a human being.

Edith Eaton worked very hard to get her writing published, even moving across the country to land a book deal. The publication of Mrs. Spring Fragrance generated press, including an autobiographical feature in the Boston Daily Globe. But after her obituaries ran, it took sixty years for her name to pop up again. In 1974, the editors of Aiiieeeee! credited Sui Sin Far as “one of the first to speak for an Asian American sensibility that was neither Asian nor white American.” In “Fifty Years of Our Own Voice,” the introduction to the landmark anthology, they quote Lummis’ on her “probably unique” characters and note how she “accurately portrayed Chinatown’s bachelor society.” Still, the rest of their commentary makes it a bit unclear what exactly readers are meant to take away about the value of Eaton’s contributions. On top of that, she is not one of the three women whose actual work is included in the book.2

In a 1981 essay titled “Sui Sin Far/Edith Eaton: First Chinese-American Fictionist,” scholar S.E. Solberg echoes Lummis’ assessment of Eaton’s “literary finish” in blunter terms. “She was not a great writer…but her attempts deserve recognition.” Perhaps it was her “integrity” that made Eaton worthy of note, if not inclusion, in a collection like Aiiieeeee!3 But a decade later, the expanded version of the anthology (The Big Aiiieeeee!) clears up some of the ambivalence of the original, laying out more directly how the editors felt about Sui Sin Far’s sensibility. She was, as Frank Chin puts it, a “lone champion of the Chinese American real.” More significantly, the new anthology includes three of her works, thus letting her words speak for themselves.

It wasn’t until 1995 that Eaton’s writing got put back into circulation through a full book: Mrs. Spring Fragrance and Other Writings, edited by Amy Ling and Annette White-Parks. Ling had published “Edith Eaton: Pioneer Chinamerican Writer and Feminist” in 1983, and White-Parks took her on as the subject for her doctoral research around that same time. 1995 also saw the publication of White-Parks’ Sui Sin Far/Edith Maude Eaton: A Literary Biography.

In the past thirty years, scholars like Dominika Ferens, Martha J. Cutter and Mary Chapman have greatly expanded our understanding of and access to Sui Sin Far’s writing, illuminating its scope, volume, and complexity. Chapman in particular has uncovered so many previously uncredited stories and essays that she has more than tripled the author’s known oeuvre. Her 2016 book Becoming Sui Sin Far: Early Fiction, Journalism, and Travel Writing by Edith Maude Eaton collects many of these writings, and its introduction argues for much deeper and wider consideration of how Eaton approaches gender, race, nationality, and genre.

Two Sisters, Two Legacies

A challenge to the claim that Sui Sin Far was the first Chinese American or Asian American author to publish a book comes from within the immediate Eaton family. Edith’s sister, Winnifred, published her first novel with Chicago-based publisher Rand McNally in 1899. Miss Numè of Japan: A Japanese Romance was credited to Onoto Watanna, the completely made-up, “Japanese-sounding” name Winnifred had been using since 1896. Winnifred experimented with various pseudonyms and published autobiographical writings anonymously, which Edith also did. But unlike her older sister, Winnifred did not acknowledge her Chinese heritage in her writing, instead obscuring it by omission, vague reference, or—in the years she wrote as Onoto Watanna—by assuming an entirely different ethnic identity altogether. Also unlike Edith, Winnifred lived into old age, published many books, and experienced a great deal of commercial success as a novelist and screenwriter during her lifetime.

We can’t know what Edith thought about her sister’s choices, or vice versa. There is no accessible archival material illuminating their relationship—no letters, diaries, etc. Though some suspect that Winnifred wrote a New York Times obituary claiming that Edith was half-Japanese (thus bolstering her own narrative), the way their professional personas bled into their private relationship is currently a mystery.4

Their published work, however, contains some clues. In “Leaves from the Mental Portfolio,” Edith explains how some who share her background may choose to “pass” in a similar way that Winnifred did:

The Americans, having for many years manifested a much higher regard for the Japanese than for the Chinese, several half Chinese young men and women, thinking to advance themselves, both in a social and business sense, pass as Japanese. They continue to be known as Eurasians; but a Japanese Eurasian does not appear in the same light as a Chinese Eurasian. The unfortunate Chinese Eurasians! Are not those who compel them to thus cringe more to be blamed than they?

Though the essay emphasizes the many ways Edith refuses to follow similar paths, the end of this passage directs the reader’s judgement quite clearly.

For her part, Winnifred gives some insight on how she viewed her older sister in the autobiographical novel Me: A Book of Remembrance, which was published anonymously in 1915 (the year after Edith died). While sitting on a park bench with a drunk suitor asleep in her lap, the protagonist finds herself reflecting on her many siblings, including:

….the eldest, a girl with more real talent than I…She is dead now, that dear big sister of mine, and a monument marks her grave in commemoration of work she did for my mother’s country.

In recent years, many scholars and critics have rejected the idea of Edith as the “good” sister (claiming her true heritage and advocating for Chinese immigrants when it was extremely unpopular, even dangerous, to do so) and Winnifred as the “bad” sister (fraudulent, exploitative) for more nuanced readings. In Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America (2002), for example, Viet Thanh Nguyen examines how critics alternately assign ideas about resistance and accommodation to the work of both sisters, often in a way that tells us more about contemporary interests than the sisters’ own.

A Web of Relationships, Distinct Voices

Edith and Winnifred Eaton’s choices overlapped and diverged in startling ways; they both lived lives for which they had no previous model.5 Much remains to be explored here. Luckily for us, Mary Chapman is currently at work on a micro history of the entire Eaton family: a large and fascinating group of people whose personal histories and accomplishments reflect how individuals shape their own worlds from shared attachments and experiences.

To kick off the preface to her biography of Sui Sin Far, Annette White-Parks quotes Dionne Brand from a session the American Studies Conference in Toronto in 1989: “We are always talking about power relationships in society; facts are never objective. Meaning that—as writers—we must always be aware of where everyone is located and at what point in time.” Brand’s instruction to consider the particulars of a writers’ place and time (down to neighborhood, job, etc.) connects to the need to, as White-Parks puts it, “point out the uniqueness of each writer’s viewpoint.” This can be a balancing act, with big stakes; as the editors of Aiiieeeee! assert: “The question of point of view is only partially stylistic in minority writing. It has immediate and dramatic social and moral implications.” It is essential to go beyond recognizing work by someone like Sui Sin Far as a “gesture.”

In the excerpt from Diana Chang’s 1957 novel The Frontiers of Love in Aiiieeeee!, one encounters a thesis of sorts on how context and connections can obscure, but also form, a distinct sensibility. The protagonist, Sylvia, is playing peacemaker during a routine parental spat that stems from the family’s very specific circumstances. Her mother is a white American woman, her father is Chinese, and the family lives in Japanese-occupied Shanghai during World War II. “Relationships were like pressures that pushed you in thirty-six directions of the compass,” she reflects. “But, as in a crowded streetcar, if you learned how to maintain your balance against all the weights, you might arrive at yourself.”

Cita Canon Spotlight

This month we’re highlighting two women whose work spanned literature and visual art.

The editors of Aiiieeeee! called Citizen 13660 by Miné Okubo (1912-2001) “the first serious creative writing by an Asian American to hit the streets.” The graphic novel features 206 drawings Okubo made while incarcerated at the Tanforan Assembly Center in California and the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah. Considered the first published account of the Japanese internment camps “by one who was there,” Citizen 13660 takes its title from the number assigned to Okubo’s family unit. While at Topaz, Okubo was the art editor for Trek, a literary and arts magazine that featured the work of incredibly influential (and also, at the time, incarcerated) writers like Toshio Mori. Prior to Pearl Harbor, Okubo received an MFA from Berkeley and studied under Ferdinand Léger before taking work creating mosaics and murals under the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Arts Project. In 1944, a job with Fortune magazine helped secure her release from internment; from there she continued her work as a painter and illustrator. In 1984, Citizen 13660 was recognized with an American Book Award and in 2021 the Japanese American National Museum held an exhibit celebrating the book’s 75th anniversary. [Miné Okubo Collection at the Japanese American National Museum]

Diana Chang (1924-2009) was, according to Aiiieeeee!, “the only Chinese American writer to publish more than one book-length creative work to date” (as of 1974) and a “well-known poetess.” Though born in New York, she moved to Shanghai as a baby and lived there into early adulthood. Her 1957 novel The Frontiers of Love is considered the first novel by an American-born author of Chinese heritage. She went on to publish five more novels and four collections of poetry. She worked as an editor for several publishing houses, edited The American Pen, and taught at Barnard College. She was also a painter, exhibiting her work in solo and group shows. Though her career was long and robust, her books, poetry, and paintings seem quite hard to find—especially online. [“First Published Asian-American Novelist, and Poet: Diana Chang” by Katie Portante for Barnard Archives and Special Collections.]

Further Exploration

To read:

An Immortal Book Selected Writings by Sui Sin Far — free online and available to order in paperback. Foreword by Victoria Namkung; cover by Shuhua Xiong. (More on the contributors in the October 2023 Cita Presss Bulletin.)

“The Divine Right of Learning, a downloadable reading companion for An Immortal Book. (February 2024 Cita Press Bulletin).

Appendix A includes the full text of Charles Fletcher Lummis’ 1900 profile of Sui Sin Far.

Appendix B features reflections from Mary Chapman, Anran Wang, Cherrie Kwok, and Victoria Namkung.

To listen:

Victoria Namkung on Sui Sin Far and a follow-up discussion with Victoria and Cita’s Juliana Castro Varón, from Lost Ladies of Lit.

Mary Chapman on Winnifred Eaton and her novel Cattle, from Lost Ladies of Lit.

“Falling Free,” a 1989 audio piece by Diana Chang preserved by New American Radio and Wave Farm.

To dig through:

“Behind Aiiieeeee!” by Tara Fickle (an archive in progress).

Topaz Japanese American Internment Camp Digital Collection at Utah State University (includes all three issues of Trek, for which Miné Okubo served as art editor).

The Winnifred Eaton Archive (directed by Mary Chapman).

Links, pdfs, images, digitized originals and more on our Are.na channel.

What Else?

Making Space for What’s Next: Free Strategy Sessions from Educopia: Educopia, Cita’s fiscal sponsor, is offering free 30-minute Office Hours with members of their Consulting team from June 9–27, 2025. These sessions are designed for individuals and small teams working through questions about strategy, structure, sustainability, or change—especially in equity- and care-centered organizations. More details about the offering, who it’s for, what to expect, and consultants’ specific skills and interests are in this blog post. Click here to schedule a session. Questions? Reach out to consulting@educopia.org

Knowing What Desires We Have Had

Knowing what desires we have had (some flaring, beautiful

ambitions),

And have had to let go,

And knowing what questions we have put off answering,

Slurring over them, always,

Seeing double, gladly,

(Fearful, unbigoted minds grasping at both sides of every

question),

It is not surprising, only regrettable that we should have come

to this.

And now we are too-far gone;

We have practiced too well a partial living.

From here, there is no recovery.

To the roomful of us, it seems always to have been this way:

You, I, and the other, manifesting conversation,

Watching the gestures of talk.

We hear the silence, uneasily,

Fearing the next pause may give us away. —Diana Chang, Poetry (November 1946)

The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu is widely considered the first novel ever written.

For more on the controversial legacy of Aiiieeeee!, its path to publication, and its continued relevance, read this excerpt from Tara Fickle’s excellent foreword to the 2019 edition, from The Paris Review.

Though Solberg’s assessment as quoted here comes off as dismissive, it’s important to emphasize that, according to various acknowledgements and citations, he provided a lot of support to Annette White-Parks and other scholars working on Sui Sin Far when there was no encouragement to do so, and that he gave Sui Sin Far’s work some of its earliest posthumous attention. Meanwhile, questions around “literary finish”etc. also align with discussion in the introduction to Aiiieeeee! about how critics approach language and style.

See Solberg, “Sui Sin Far/Edith Eaton: First Chinese-American Fictionist,” MELUS, Volume 8, Issue 1, March 1981, Pages 27–40, https://doi.org/10.2307/467366

They both worked as columnists for the same newspaper in Jamaica, for example!

This was super interesting, thank you for such a detailed writeup!